“Go!” yells Hector Guadelupe at his screen. The young, white couple in the makeshift outdoor workout space before him – clearly, a well-furnished porch in more normal times – lurch into a spasm of fast paced, unsyncopated jumping jacks. Hector hovers over his computer, his bulging biceps allowing him to float above the action. His eyes fix onto the placement and fluidity of the couple’s movements, searching for ways to improve their form while he continues to shout words of encouragement.

“We don’t know how long this is going to be but one thing is: You’re in control of your time. This is a time for growth. These minutes, like, really count still,” he assures the now huffing pair.

As they are still pumping away, Hector secures his reverse-style ball cap and transitions his body, horizontally prone, into a rigid plank, before he starts to effortlessly move one knee up toward his chest and then the other, tossing out instruction.

“Squeeze your glutes hard, squeeze your core, so you’re solid from top to bottom,” he coaches.

Hector’s motions are rhythmic, almost hypnotic to watch on the CNN clip capturing the session, with hardly a breath much less a grunt or any indication of sweat. His clients, on the other hand, don’t seem to be having such an easy a time of it but his upbeat patter keeps them moving.

“This nonsense we are going through,” Hector adds with his signature optimism, “is part of life.”

Nonsense? It may sound like Hector Guadelupe is a COVID-19 sceptic, belittling the challenges the pandemic has brought to his clients and millions of others. But that is far from the truth. At 42, Hector is merely showing the disproportionate wisdom of his few years of life, ten of them spent in federal prison and more than a quarter of that time, in solitary confinement.

Nine hundred and forty days, locked in a 6 foot by 9-foot cell sounds like a lifetime of pain. Twenty-three hours a day, five days a week, and twenty-four on Saturdays and Sundays. “No air, no shower, no this, no that,” Hector recalls. Nothing but his mind, his body, and plenty of time. Brutal, yes, but it was all he needed, he learned, to channel his preternatural drive into transforming himself, physically and mentally, into a more powerful, self-confident, and purposeful human being.

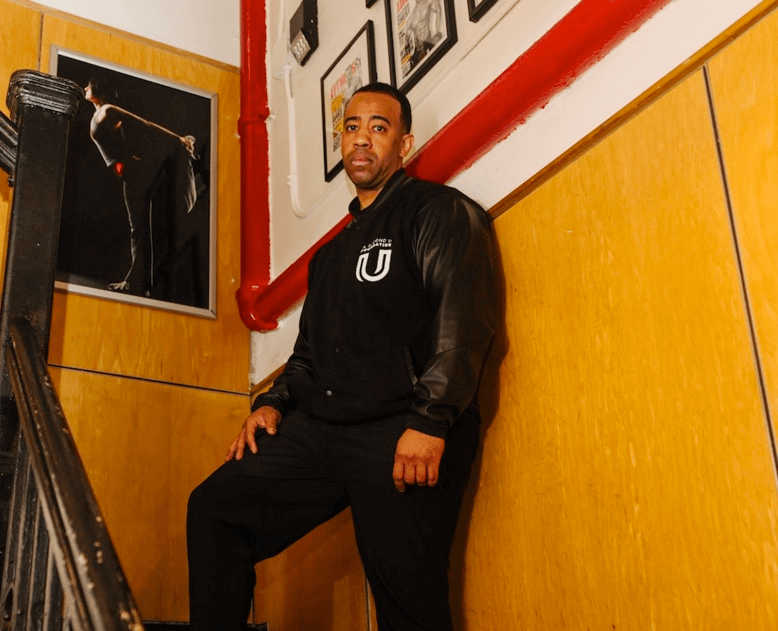

It’s that same level of physical and mental authority, topped with a deep sense of personal mission, that has led Hector to where he is today, well beyond the mental and physical confines of the prison walls, sitting astride two organizations as founder and untitled president of each: A Second U Foundation, a 501 ©3 that, as its names suggests, offers former prisoners a chance at reinvention, preparing them for well-paid positions in the $30 billion-plus fitness industry; and Unibody Fitness, a personal training business whose small staff is exclusively Second U graduates.

Both enterprises are steeped in Hector’s own brand of mind-over-matter culture, emphasizing the critical importance of integrity, teamwork, empowerment, tenacity and results. Altruism is also key. “This isn’t only certifications,” one Second U coach says in a recent CNN interview, “this is like Big Brother.” Prison and other personal experiences are incorporated, not ignored. It all adds up to what Hector, ever the businessman, sees as his competitive advantage. “The difference between everybody that comes through our hands and myself, versus the kid that comes straight out of college with an exercise physiology degree or exercise science degree, they have no life experience…they’re all textbook. If you’re just textbook with no experience behind you, you’re short…If you sat down with me and we had sessions once a week, because of what I’ve experienced in life, you’d be getting a therapy session and a training session in one.”

In today’s uncertain, socially distant, and often space-constrained environment, Hector’s distinctive approach has made him, and his team not just prepared for the pandemic, but poised to flourish in it. His glad-handing sales technique hasn’t hurt either; he knows how to turn it on. There’s more than a bit of swagger as he recalls his earliest sales: “I could read people in like the first five minutes of them opening their mouth. I was really good at manipulation…[and] I knew how to motivate people.” It’s a skill he applies to prospective and current clients, as well as his crew at Unibody and Second U. “Hector’s the best,” crows Jason, a Second U grad and Unibody trainer. “Hector’s the bus driver, the innovator” he laughs. “I’m just the passenger. And he drives you to be your best.”

“You learn that there is power in the struggle,” Hector say with an unexpected seriousness in his voice – a lesson that, with all the cajoling and encouragement, Second U and Unibody hope to share with anyone who comes their way.

——

Hector Guadelupe’s introduction to life’s challenges came early, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, then a blighted, multi-ethnic community of Blacks, Latinos, Hasidic Jews, and others, that was a far cry from the gentrified brownstones of today. Everyone seemed to be on the take, cops included. Lawlessness was the norm, as was violence, a given byproduct of the desperation, economic despair, and drug trafficking that filled the streets. Cocaine – and by decade’s end, crack – was king, the primary currency of the neighborhood, the fuel of the local economy, and the area’s number one export to more affluent addresses in the city and beyond.

As long-time activist Al Sharpton told a reporter “People say that Manhattan was dirty and dangerous in the early ’80s, and I just have to laugh…Things were 50 times as bad in Brooklyn as they were in Manhattan.”

This was young Hector’s world.

Hector’s family – mother, father, grandparents and great-grandmother – were close at hand if not fully intact. Everyone worked at something. But life was far from settled. His father was absent much of the time, soothing emotional wounds he suffered from multiple tours with the Marines with heroin and crack cocaine. He would try to come clean on occasion and attend narcon meetings. But it never stuck.

Hector’s mother was at home, at least physically, until drugs began to eat away at her life as well. “My parents always hosted,” Hector says, matter-of-factly. “There were always parties and there was always lots of coke. It was all right there in front of me.”

Coke likely contributed to Hector’s dad death when the boy was just 8. Cancer, and probably drugs, took his mother only four years later. Left to live with his grandparents, Hector, angry and increasingly reckless, began to lash out. “You don’t care about nothing when you’re in pain,” he recalls. “Nothing matters when you are in the mindset. It’s sad.” By 13, he fled. “It was rough,” he admits.

He found some footing by dealing. He had the chance to earn some money, a bit of pride, and some street cred. And he discovered community. Older guys, bigger guys, guys with gold chains and money clips of big bills, had his back. “There is a community – weird sense of community,” Hector says, “where people from other neighborhoods will say ‘don’t fuck with those kids’”. This is just something that is understood. Law enforcement understands. It’s like a weird underworld.”

Hector was good at what he did. Really good. He learned by watching successful dealers and applied their business basics to creating something of his own. He was relentless and self reliant. “You don’t have no way to get out of that neighborhood. You don’t have nothing. You have no resources. Who’s else going to get you out of that neighborhood?” he asks, not at all rhetorically today.

Looking back, he makes it sound easy: “You gotta really know how to structure it first. Where do you need lookouts, who’s going to do the accounting, who’s going to bag up all the work. It’s like putting together a business plan.” What made him so determined? “Growing up with too many roaches in the house,” he chuckles now. Then, more seriously he adds: “When you grow up poor, there are many people who want it but they don’t know how to go about it..It’s not taught, it’s something that’s in you.”

By 17, Hector’s dreams were becoming more of a reality. He had his own bachelor pad and swarms of college girls cozying up to him, as clients and as friends. “I just fucking love women,” he says with a wink and a “ha! On the business front, he also had dozens of salespeople, and a burgeoning operation that ran almost the full length of the East Coast, from Cape Cod to Miami, and west of Chicago. He was running upwards of 30 to 40 kilos of cocaine a week, clearing

$30,000 a pop – a decent paycheck for someone who wasn’t even old enough to vote much less clear the graduation bar at his high school. It felt good. Maybe a little too good,

——

No one would come to Sunbury, Pennsylvania, population 9,000, without a reason. There was nothing noteworthy about the town. In fact, it was effectively nowhere, tucked away in a remote stretch of the central part of the state, perched on the eastern shore of the Susquehanna River. But nowhere was exactly where 22-year Hector wanted to be when he was tipped off that the feds were finally after him.

“It was snowing really bad,” Hector recalls, “and I had a girl pull up who was coming to visit. I remember looking out the window…and across the street there was like some dude that was acting like he lived there and was hammering something on the side of his house. It’s like no one is fixing shit at that point outside of their house in wintertime in the middle of a snowstorm. It was just very odd to me. It was like my Donny Brasco moment.”

Within hours, dozens of federal agents and military personnel were at his door, storming into the small three-bedroom house that Hector had rented. He laughs when he recalls that he was smoking a joint when the feds barged in, then adds with some degree of “you don’t scare me” pride and lasting distrust of the police: “I was still smoking when we left.”

For the hustling, coked-up, young prince of the East Coast drug trade, federal prison was a crash landing. The mind-numbing monotony of each day and the complete absence of freedom was a drag on the soul. While there was nothing to run from, there was also no dream to run toward.

“You don’t know what to think,” Hector remembers. “You don’t know what to feel.”

After a year of zombie-like existence, something in Hector clicked. He started focusing on the things he could control: the importance of his health and working out. He began to practice meditation and sought to redirect his frame of mind. “I said okay, the only thing I cared about was working on myself.” He dropped, 90 pounds, started learning about “yoga and all the good things,” he says almost wistfully. “Fitness was my refuge. Even emotionally, it helps. It builds character; it builds discipline; it builds confidence. And you have to actually stay strong in case you have to defend yourself one day.”

Hector, the entrepreneur, caught on to the fact that there was plenty of money to be made, too. “Everybody has money in prison,” he explains. “From their accounts, their families, money that they stashed, you know. Enron guys was in there with me, Jacob the Jeweler was in there with me. From kingpins to Wall Street, they all in there.”

Hector couldn’t help but to capitalize, in ways that were legitimate and some that were not. He bribed someone $1,000 to secure the job of managing the gym. From there, he launched an above-board training business and built a team of other trainers. He was given permission to charge, which he did, on a Hector-made sliding scale, offering services gratis to the guys who couldn’t afford much – especially guys from his old neighborhood, – but charging often hundreds of dollars to the financial big wigs. “I won’t even tell you who I trained,” he adds with a satisfied smirk.

Still, Hector couldn’t resist the unsanctioned trades. He pedaled in porn (“yeah, you can imagine that was big there’) and phones and watches and tobacco. “A package of smokes would run you $250. Yeah, if you didn’t have money, you wasn’t smoking.” Business was great, until just like on the street, it wasn’t. Hector was outed and thrown into solitary for 31 months, years that would prove strangely fruitful for his mind, body and soul.

By the time he was released in 2012, almost exactly 10 years to the day he went behind bars, Hector was a certified fitness instructor with business plans in hand. “I just felt so much more confident, so much more powerful,” he says with satisfaction. It took almost a year to get a job, long months of turn downs and suspicious looks, until he finally found a taker, a manager at a Union Square gym who was willing to look past his criminal record and to give him a chance as a personal trainer. He did his time, from eight in the morning until eleven o’clock at night. Six or seven days a week, Hector never let up. “Hey,” he laughs, today “it was better than solitary!”

Barely a year later, with advice and encouragement from one of his first clients, he hired and trained seven men, all ex-cons like himself who were stymied by employers who couldn’t get past their records. “People should not be defined by their sentences,” Hector says emphatically. Like that, Unibody Fitness, was born. Months later, looking to spread the opportunity to other former prisoners, the Second U – as in another chance at becoming a fully realized you – took shape.

——

Today, Hector slurps on a well-earned margarita at the end of another 10-plus hour day and recounts the results he and his team have achieved so far. Just five years in, Unibody boasts hundreds of happy – and now, more fit – clients. In an even shorter span of time, Second U has produced almost 200 fully trained and licensed fitness professionals, all inmates coming off of up to 20 year sentences, men who stepped out from behind bars with very few prospects of even a low wage job, much less one that promises a living wage earning $35 to $75 an hour like they do now. Not one of them has returned to prison, much less had a run in with the law, defying nationwide statistics that routinely show a 30% plus recidivism rate.

Clients feedback has been only positive as well. Having an outlet during the past eight months has been a relief – “it works both ways,” Hector adds, assuringly – and they are especially grateful for the reminder that current conditions seem small next to what their trainers have lived through. Says one young woman, in a recent news clip: “It just helps you shift your perspective, so you have a little bit more gratitude.”

Hector takes another sip before quickly reeling off other ventures that are already underway. There’s the street’s-view podcast of Brooklyn in the late 70s and early 80s that he is developing. The negotiations with a high-profile media family to support a housing initiative for ex-cons. And his core business at Unibody, having already tripled during the pandemic, is prepping for a national roll-out along with Second U as well.

“Wellness is about more than taking care of your body and eating right,” Hector notes. “It’s about what are you doing to better your people.” Every one of his plans seems to embody that mantra to a tee.

“I tell my people, we gotta deal. And we’re a community. And we gotta rock this shit just like we’re gonna rock this workout tonight.”